The Longfellow Effect

No single book has influenced the geography of south Minneapolis more than “Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Hundreds of streets, schools, lakes, waterfalls, neighborhoods, and more have been named after its characters. And he never even set foot in the state.

Longfellow was a literary celebrity after publishing many various works of poetry. Writing at a time when poetry was mainstream and a popular intellectual pursuit, Longfellow used the medium to publish works supporting political aspirations like the abolition of slavery. He had published many translations of classical works like Virgil’s Odyssey. He had also published poems capturing the patriotism of a young America like “Paul Revere’s Ride”. In 1855, he published his epic poem set in Minnesota capturing the love story between Hiawatha and Minnehaha. Soon after, Hiawatha mania swept the nation.

Longfellow saw a need to record native american stories before they were lost. He was captivated by them and sympathized with them as they were being forced from their homelands and their culture erased. Unfortunately, while he had taken it upon himself to record native american stories, his artistic aims outshone any desire for accuracy. Longfellow took stories from many different tribes and mixed and matched as he pleased. He never, in fact, visited the territory where most of his stories are set but instead based his writing off of the notes created by Henry Schoolcraft when he explored and mapped the Northwest Territory.

The “Song” main character, Hiawatha in fact a real Iroquois warrior, but his name was given to the Ojibwe trickster, Nanobozho. The princess Minnehaha is a fictional character based on the Dakota word for waterfall. Nokomis, the Ojibwe phrase for ‘my grandmother’ became the grandmother’s name. Keewaydin is the northwest wind.

Today we would not consider poetry a popular pastime, but in Longfellow’s era it was a national obsession. Recitation and classroom elocution exercises were standard practice. Public gatherings and parties often featured a poetry reading of some kind. Civic-mindedness and a desire to build a sense of community was a cultural movement in an America that was a “melting pot” of various and disparate immigrant cultures. Longfellow’s story romanticized the community-minded culture of native americans. The country was changing, growing rapidly, and on its way toward Civil War. They embraced the feeling of nostalgia for these “people of the past”.

They also embraced the racist ideals of white Christian “Manifest Destiny” folded into the narrative. When Hiawatha peacefully and willingly rides off into the sunset in the end, it assuaged any American guilt towards these peoples that they were annihilating. As America expanded westward, Native Americans would accept their fate and conveniently disappear. Native Americans are still very much around, but some people still tend to use this romanticized image of the "noble savage" in order to sweep them into the past.

On the other hand, critics panned it. They could not believe that Longfellow had seen fit to memorialize any aspect of Native American culture that, at the time, was being so actively campaigned against with negative propaganda. Longfellow’s epic was the antithesis to the savage, violent, stupid, unromantic race that was being “justly exterminated”. In short, it wasn’t racist enough for them.

Still, it was embraced and took on a life of its own. Composers set it to music or created compositions inspired by it. The second and third movement of Antonín Dvořák's Symphony No. 9, From the New World are based on it. Later, Duke Ellington and Johnny Cash would write songs referencing the poem.

The tom-tom rhythm of the poetry made it easy to recite and remember and it became a popular community activity. In Pipestone, Minnesota, the annual performance and recitation was a tradition for 60 years before finally bowing to changing cultural opinions and waning popularity and closing in 2007.

Today, these place names are engrained in our culture. The sheer number of places, institutions and business that are named after the characters of Longfellow’s story is astounding - and not just in Minneapolis, but worldwide. Still, it is important that we don’t confuse the mixed up mythology created by a white author with the vast breadth and depth of native spirituality as well as the living, vibrant cultures that are all around us.

The Longfellow House

You can’t tell the story of Longfellow’s influence on Minneapolis without mentioning the Longfellow House. When we think of the Minnehaha Falls Park today, we think of grabbing a bite and a beer at Sea Salt, having a a picnic in the shade and leisurely walks along Minnehaha Creek. The park is a peaceful place to spend the day. But in the early 1900s it was a zoo. Literally, a zoo.

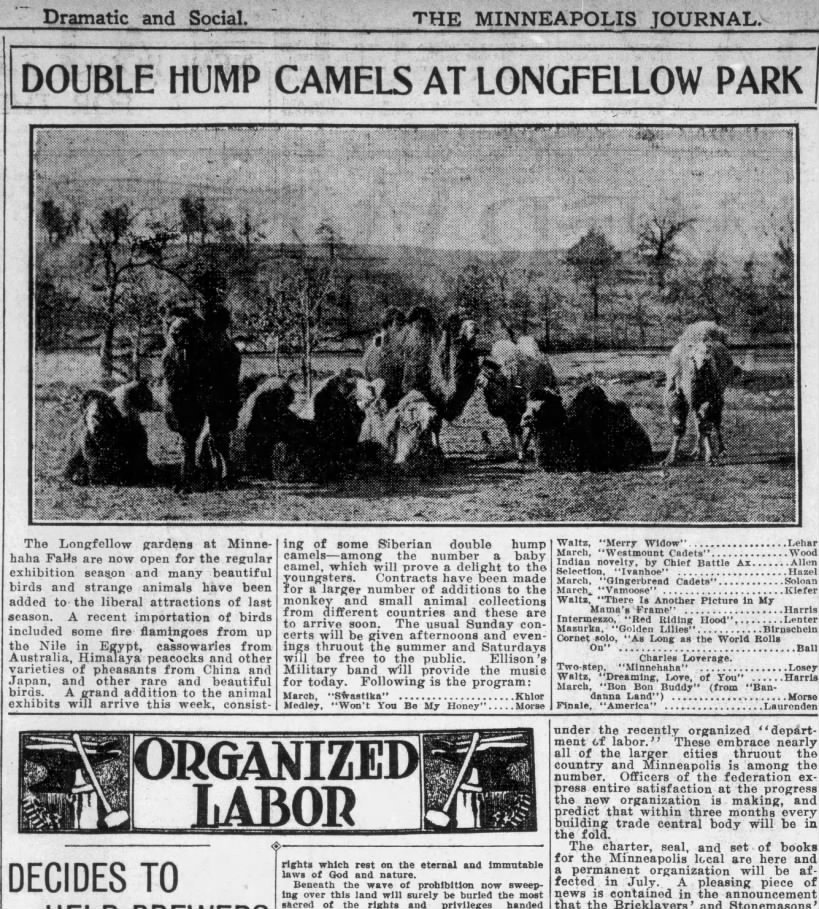

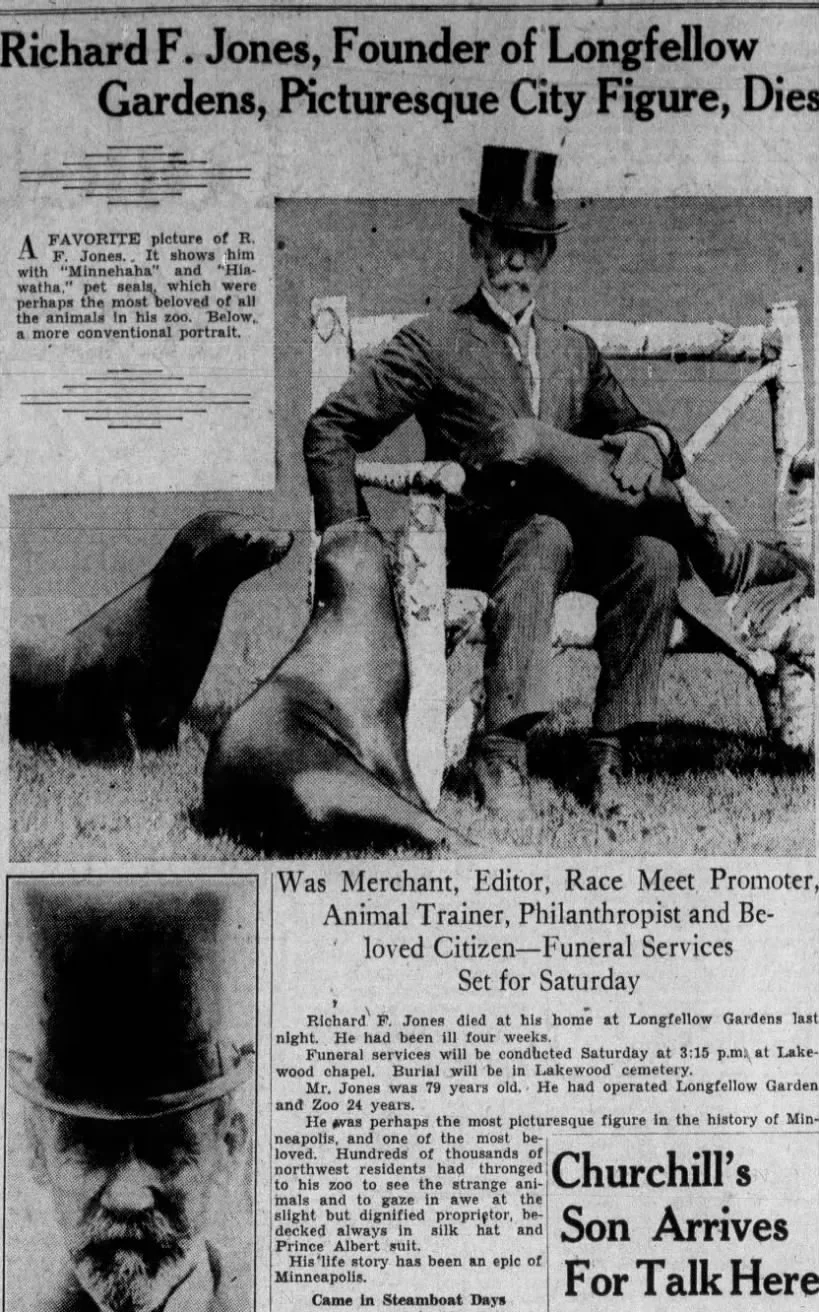

Robert Jones, nicknamed “Fish” because he had made his money running a fishmarket downtown, ran a zoo on the grounds near the falls from 1907 to 1930. It started with his private collection of exotic animals. Bird enclosures held species from near and far. A seal act in the lagoon starred sea lions (problematically) named after Longfellow’s characters. Deer and elk lived in pens downstream from the falls. Camel and elephant rides, along with a miniature steam train, snaked through the crowds. An arena seating a thousand spectators held afternoon shows starring lions, tigers, and bears (oh my!).

Jones’ family lived nearby in a replica of Longfellow’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is said that Longfellow was Fish’s favorite poet, but I think it’s more likely that he saw the marketing possibilities from the authors’ popularity. The replica home was built at ⅔ the size of the original - but has the same layout and features.

Over the years, the neighbors tired of the Longfellow Gardens. They were noisy, smelly, and on more than a few occasions, animals had escaped the grounds. Jones made a deal allowing him to keep operating the zoo for ten years, but turned over ownership of the land to the city. A few years after Jones’ death, the zoo was closed and the buildings torn down. For a time, the Longfellow House became a public library. In the 70s, it sat empty - except at Halloween when it was used as a haunted house.

In the 90s, the house was moved closer to the falls because of the expansion of Hiawatha Avenue. It was renovated and is now offices for the Minneapolis Parks foundation and houses the Minnesota School of Botanical Art. Today, the statue of Longfellow that was a centerpiece of Longfellow Gardens sits in its original location, alone in a field on the wrong side of Hiawatha Avenue. Siding and trim repairs are in progress and it will soon get a fresh coat of paint - keeping this reminder of the Fall’s “wilder” past at its best.