Radisson - The Original

I have to confess that even though I have lived in Minnesota for over twenty years, I did not realize until just recently that before there was a worldwide chain of more than 1400 Radisson Hotels, the very first Radisson Hotel was built right here in Minneapolis. Although the Radisson name is commonplace, its origin story is not.

In 1907, Edna Dickerson received a multi-million dollar inheritance from her cousin Albert Johnson. Albert was a pioneer who had arrived in the Minnesota Territory in 1855. A real-estate lawyer by trade, he spent his life buying land throughout the state and across the country, building his fortune. Well-known throughout the state as a quirky but honest businessman, Johnson was a lifelong bachelor. His death was caused by a severe case of pneumonia that developed from a cold caught while traveling through California, Utah and Colorado. Edna stayed with her uncle through his illness and was rewarded for her devotion with the bulk of his estate. Albert had always been impressed by Edna’s work ethic and success as the owner of a business in Chicago.

Minneapolis businessmen immediately began lobbying the heiress with how they thought she could invest her newfound wealth. Among them was George Draper Dayton, whose Dayton’s Department Store sat next to an empty lot that Johnson had owned and passed on to Edna. The plot of land around the corner would be the perfect spot for a much-needed hotel.

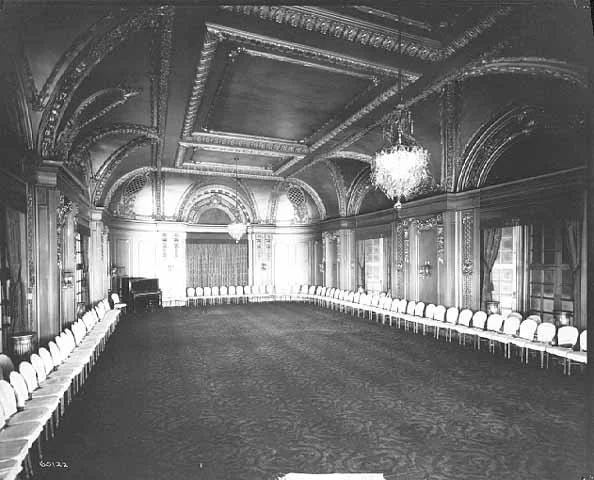

Convinced, Edna invested $1.5 million of her inheritance in building the luxury hotel and construction began in 1908. Pulling out all the stops, the French Renaissance style architecture was set off by period furniture, parquet floors, Circassian walnut walls and a lobby lined with pink and gray marble. At sixteen stories, 425 rooms, the hotel was the second tallest building in the city at the time (City Hall was the tallest). It had all the amenities and more: a cigar shop, a Viking Ship, an artesian well, a library, and each room had its own telephone. Edna and her new husband, Mr. Simon Kruse, decided to manage the business themselves and resided in apartments in the hotel.

Of course the new hotel needed a name. The Commercial Club of Minneapolis, a mens’ club for local business owners, was going to occupy the top two floors of the hotel for their clubhouse. The club suggested the name “Radisson”in honor of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, the first white European to reach Minnesota territory. To advertise their choice, the club took advantage of a popular hobby of the times: an essay contest. High school students were invited to compose essays about the historic figure and the winners would get a cash prize. Thirty-one students submitted compositions and the winner was a junior from North High School named Ruth Hanson. For her efforts, she received $12 and her essay was displayed in a framed case in one of the hotel's corridors. Her essay was also published in its entirety in the newspapers. There was no way for the Commercial Club or the Kruses to anticipate how their chosen namesake would become a household name or how his true life story would be revealed.

On its merits, Ms. Hanson’s essay is very well written. “A clear-cut, straightforward, simply told tale” is a fair appraisal. Unfortunately, one thing it is not is complete.

As is often the case with historical essays, especially those that are meant to be written to honor their subject, it is just a sketch. The basic outline of the person is shared without any of the details, especially the less socially acceptable aspects of their life story. Most likely, Ms. Hanson was working from an approved textbook or other materials provided by her teachers or the local library. Luckily for us, we have access to the actual diaries that Radisson wrote throughout his life. Following the outline of Ms. Hanson’s essay, let's fill in the details that her essay left out.

Ms. Hanson starts off her essay describing the “untrammeled wilderness” but we all know that it was in fact well-populated by the Ojibwe and Dakota. Radisson and Groseilliers were not the “first men” to see what would become Minnesota. Omission of the existence of Native Americans was just a typical occurrence of the era and we have all become used to correcting the record on who was here first - Native Americans lived in North America for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans - but the factual error should still be pointed out.

Radisson’s Early Life

The essay recounts Pierre’s early life and provides all the basics. It glosses over, however, Pierre’s experience as a captive of the Mohawk tribe. In reality, Pierre’s experience provides much more insight into his life and character.

Pierre-Esprit Radisson was born in France in approximately 1635 and was shipped off to New France around the age of 14. Living with his half-sister in the village of Trois-Rivieres, Pierre was one of only 3000 French men, women and children spread out among the tiny settlements of Quebec and Montreal in 1852. While out hunting one day, Pierre’s friends were killed and he was taken captive by the Mohawk tribe of Iroquois indians. Luckily for Pierre, instead of being killed he was adopted by the tribe and spent over a year immersed in their culture. He was treated like a prince by his adoptive mother and sisters, groomed and lavished with gifts of furs, wampum, and other adornments. Still, he was their captive and he was forced to make hard choices. The tribe lived off the land and during the winters often suffered. Pierre recounted participating in a winter war party that went terribly wrong, forcing the men to not only boil deer droppings to eat but also to kill two women who were their captives and make broth from their bodies. This was Pierre’s first self-confessed act of cannibalism, an act he would resort to multiple times in his challenging life.

Pierre made his first escape attempt in the fall of 1652, but was recaptured. As punishment, the tribe put him through horrific ritual torture. Tied to a scaffold in the village, his facial hair and fingernails were pulled out, he was beaten and shot with arrows, he was burned numerous times and a sword was driven through his foot. Miraculously, Pierre survived and was welcomed back into his adoptive family, who nursed him back to health.

He made his second, and successful, escape attempt later that year. Saved by Dutch traders, Pierre traveled to Holland but quickly returned to his family in Trois-Rivieres. By this time, Pierre’s half-sister, Marguerite, had a new husband: Médard Chouart des Groseilliers.

Médard was by all accounts a “character”. His name by birth was Médard Chouart, but he gave himself the title, Sieur de Groseilliers - “Captain Gooseberry” after he bought a farm near Trois-Rivieres. He was also known as a terrible father. He abandoned his eldest son, also named Médard, after his first wife’s death. After marrying Marguerite, he sent off her two oldest boys to foster homes. For Marguerite, in early New France, there weren’t a lot of choices and Médard had income from a farm and from work he did for the Jesuit Priests. By the time Brothers-in-law met in 1654, Médard had already explored deep into the western territory of New France and was readying to go again.

The First Voyage

Ms. Hanson’s essay says that “one finds that the first expedition, presumably between the years of 1654 and 1656, took them into the territory west of the Great Lake”. Although Pierre wrote extensively about this trip in his journals, historians have a hard time agreeing on where Pierre actually was during these years. Some believe Pierre didn’t go on this trip at all. Journals written by Jesuit priests from the same time period record Pierre being with Fathers Paul Ragueneau and Joseph Inbert Duperon on their mission to the Onondanga tribe. Did Pierre get the dates wrong? Was he lying? We may never know, but most historians agree there are problems with Pierre’s timeline.

The Second Voyage

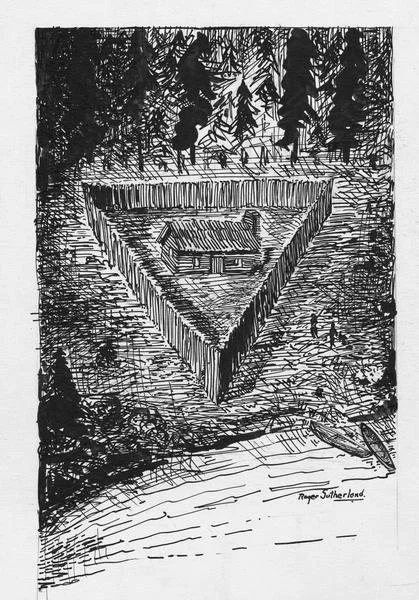

It was in 1658 that historians have confirmed that Pierre and Médard actually teamed up to explore the Great Lakes and find a way to cut out the middlemen, the native americans, from the fur trade. They reached Lake Superior, saw the Pictured Rocks, and Pierre rather boldly named the Portal of St. Pierre after himself. (The name didn’t stick and is now known as Grand Portal Point). When they reached Chequamegon Bay in what is today northwest Wisconsin, they built what was then the most western log cabin fur post. Here, the explorers made contacts with the Cree, Menominee, and Sioux tribes who told them about the “Northern Sea” or Hudson Bay, but it is unclear whether they actually traveled to the bay on this trip or not - although they would definitely see it in person on future voyages. It was on this trip that Pierre and Médard met with the Sioux at Knife Lake in Kanabec County, Minnesota, making them the first white men to travel in what would become Minnesota. It was also during this trip that they encountered the “various Indian customs and manners which seem to have been an unending source of information and amusement” according to Ms. Hanson. These amusements, described in much more detail in Pierre’s journals, included both of the men having sex with many native women, taking wives among the tribes (making Médard a bigamist), participating in murderous war parties, and continuing to take part in cannibalizing their enemies.

On this voyage was also when Ms. Hanson relates that Medard and Pierre saw the “Great River” and even traveled as far south as Prairie Island near Red Wing. Historians can’t seem to agree on whether this actually happened. Some believe Pierre’s vague descriptions and inaccurate place names mean they only saw the river in northern Minnesota. Pierre also claimed that they made it all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, but there just wasn’t enough time in the events of this voyage for them to have traveled so far south, then so far north and back again. His inaccurate descriptions of the weather, plants and distances, were figments of Pierre’s imagination. Why would Pierre make such a wild claim?

Ms. Hanson uses quotes from Pierre’s memoirs that describe the wonders of the Minnesota territory that seem as if he were writing a travel brochure. In fact, he was writing a business proposal. At this time in the history of New France, nearly the entire colonial settlement was owned and financed by a company of investors. Known as the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, or Company of 100 Associates, 100 French investors were given a monopoly on all trade in New France in return for increasing settlement there. So far, they had seen little return on their investment. Ready to give up on ever making New France profitable, the Company was relieved when Médard and Pierre returned to Trois-Rivieres in 1660 with over 100 canoes full of furs and describing the riches that could be had from the western lands. They were welcomed as heroes. The settlement was in dire need of a source of income and the rogue fur traders had saved the day.

Their heroes’ welcome was short-lived as the governor imposed enormous taxes and fines on them because they had not sought permission from the government prior to their trip. Médard was also thrown in jail for deserting his post as Captain of the Garrison. By law, he should have been shot for his crime, but was given clemency because of the value of the goods he and Pierre had brought back. After Groseilliers appealed directly to the King in France and got their money back (but then lost it in a bad business deal), Pierre and Médard conspired again to illegally travel to the interior, reach Hudson Bay, and smuggle furs. Thwarted by the Jesuit Priests who saw them as competition for the furs that would finance their missions, Médard and Pierre made a move that they would surprisingly make again and again. They decided to work for the British.

Treason - Round One

Ms. Hanson says that they decided to “transfer their allegiance”, but changing loyalties and going over to the British wasn’t just like we think of changing employers today. Nearly all business was owned and controlled by either the French or British crown, so going to the other side and sharing inside knowledge of business operations was actually an act of treason. And so it was with illegal British support that Pierre and Médard eventually made several trips to Hudson Bay and laid the groundwork for what would become the Hudson Bay Company in 1671. They supplied the British with the working knowledge necessary to help the British succeed in the New World while letting their own countrymen struggle to survive. Although Ms. Hanson’s essay says that this was a “commercial power, which they would have preferred to bestow on their own country”, in truth Pierre and Médard would have sold their services to the highest bidder, no matter their country of allegiance.

Still, in return for their hard work, literally risking life and limb while betraying their country, Pierre and Médard were shortchanged by the Hudson Bay Company. The investors were given stock options, but they were not. Their frustration increased as they were slowly pushed out by members of the company who were becoming familiar with the trade routes, making their own connections among the tribes they traded with, and no longer needed the explorers as guides.

Treason - Round Two

Their exasperation led to their second act of treason - returning their loyalties to France in 1675. In doing so, Pierre also abandoned his English wife, Mary Kirke, and child. Mary’s father would not let his daughter and newborn grandchild be dragged off to France. Desperate for work, Pierre left Médard behind and joined the French Marines. He was sent to fight in the Caribbean as the French tried to push the Dutch off of the islands there. In 1678, the fleet of ships Pierre was traveling with shipwrecked on the coral reefs of Las Aves. Stranded for weeks, Pierre survived while over 1000 of his fellow marines died of starvation. (I think you can guess how Pierre survived).

While Pierre was on this Caribbean Cruise from hell, other French explorers were continuing where he and Médard had left off. La Salle, Marquette, Joliet, Hennepin, and Du Lhut were all making their mark on the future state of Minnesota. In 1680, Pierre and Médard reunited and, joined by Médard’s adult son Jean-Baptiste, made another trip to Hudson Bay and for a short time were able to play both sides of the fence working with the Cree, the French and the British all at once. But Pierre got too big for his britches and in the name of France took the British captive, seized their ships and returned to Quebec. Instead of being welcomed as a hero, the captives were freed and Pierre was sent to Versailles to answer to the King in person. At this time, France and England were at peace, the two Kings were cousins, and Pierre had risked starting another war. He was given one last chance to go to England and patch up his marriage, then get back to France and behave.

Treason - Round Three

In 1684, after failing to save his marriage with Mary and getting in trouble with the French, Pierre resorted to his usual tricks and changed sides - AGAIN. Back on the side of the Brits, he sailed back to Hudson Bay and found the French troops (now led by his nephew Jean-Baptiste) he had left there. Once his allies but now his enemy, Pierre robbed them. Officially sick of Pierre’s antics, the French governor of New France put a price on his head. Quickly sailing to London to beg King James for forgiveness and plead his innocence, Pierre found that his wife, Mary, had died. No bother, he married Charlotte Godet the same year.

In 1687, apparently unphased by the very real fact of people sailing around seizing ships hoping to find him aboard and kill him, Pierre returned to Hudson Bay yet again. He resumed trading for a while, but it was not, shall we say, a “supportive work environment”. Frustrated by the politics of working for what had become a large operation without the respect he felt he deserved, Pierre sailed for London. He would stay in England the rest of his life. A price on his head in Quebec, charges of treason against him in France, he gave up any connection to France and became a naturalized British citizen. He spent years fighting the Hudson Bay Company for money he felt he was owed and in return the Company gave him a minor yearly allowance. He and Médard fought hard to get the credit they felt they deserved in founding the Company, but were ignored. Médard Chouart des Groseilliers died in 1696 on his farm in New France. Pierre-Esprit Radisson died in London in 1710.

The Explorers’ Legacy

Pierre and Médard’s actions had consequences long after their deaths. France and England were both claiming sovereignty over the territories the men had explored. Both countries laid claim to the land around Hudson Bay - England because the land was explored under the Hudson Bay Company Charter, France because the people who did the exploring were French citizens. Since the men had changed loyalty so many times, it all became a murky mess. The men’s actions also had consequences for the Native American tribes they had interacted with. The war parties they had joined motivated revenge from their enemies and led to intertribal wars. They set off chain reactions that lasted for decades.

Now that historians have had a chance to examine Radisson’s journals and cross reference them with other historical records, we know that Radisson’s retelling of his journeys are full of inaccuracies and false claims. Some historians kindly attribute Pierre’s false claims to bad memory since he wrote his journals ten years after the fact. Others are less apologetic and believe Pierre’s lies about his accomplishments were a part of his self-aggrandizing plan to gain financial support. Analysis by experts has exposed that Pierre appropriated stories from people he met on his travels, embellished others, and even jumbled up the timeline of the stories he did actually live himself.

Radisson and Groseilliers led extraordinary and eventful lives, but it is a mistake we often make, looking back and ascribing heroic motives to the actions of others. Pierre and Médard were not “explorers” of bravery and selfless deeds. They were two ordinary men looking for opportunities to get rich. We can’t blame the Commercial Club or Ms. Hanson for choosing to honor Pierre-Esprit Radisson. Especially in the context that Pierre’s journals had only been published in 1885, giving only a little more than a decade for his legend to spread around the world. All they knew was that these two men had accomplished a “first” in Minnesota history. Today we may cringe at the choice to make Radisson a worldwide brand name, but at the time it made perfect sense.

The Hotel’s Legacy

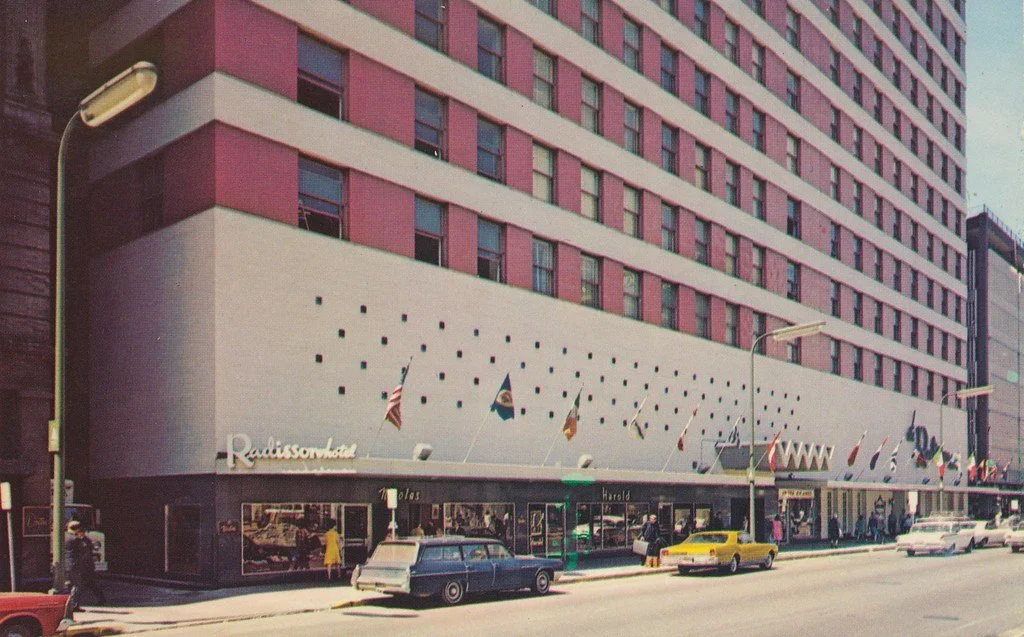

In the end, after Edna and Simon Kruse managed the Hotel Radisson for 25 years, hanging on through the Great Depression, it was lost to the mortgage company in 1934. After a few private owners, it was then bought by the Minnesota-based Carlson Companies in 1962. Led by Curt Carlson, they began opening Radisson Hotels across the country and around the world. The original Radisson Hotel was remodeled in the 60s, but ultimately demolished in 1982.

The new Radisson Plaza Hotel building was remodeled and rebranded as the Radisson Blu in 2014. In 2021, it was rebranded again as the Royal Sonesta - the first time in 114 years the building did not have the name Radisson over its doors. Still, I am 100% sure that Pierre-Esprit Radisson would get quite a kick out of knowing his name is on hotels around the world - and he’d probably think he deserved it. Do you?