The Saint Anthony Falls Have Moved

Saint Anthony Falls, or Owamni, is the core of downtown Minneapolis and was the number one reason for the development of the city. Even today, the waterfall is the center of activity with walking and biking paths snaking along the riverbanks. The Stone Arch Bridge, crossing the Mississippi and providing views of the falls, is a widely recognizable landmark.

Tourists and locals alike enjoy visiting the falls and experiencing first hand the power of the water rushing over them. But did you know that when Louis Hennepin famously first saw the falls in 1680, they were actually in a different place?

Geology at the Falls

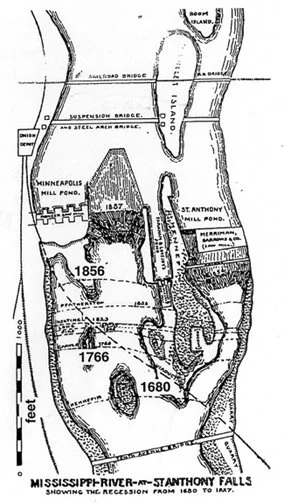

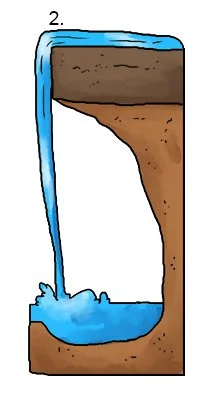

That’s right, the falls have been on the move for about 12,000 years. That’s because of the geologic structure of the rock underneath. The falls flow over a layer of limestone and shale. Water gets into tiny cracks and under the limestone and washes away the softer shale and sandstone underneath. When enough of the sandstone support is gone the limestone collapses.

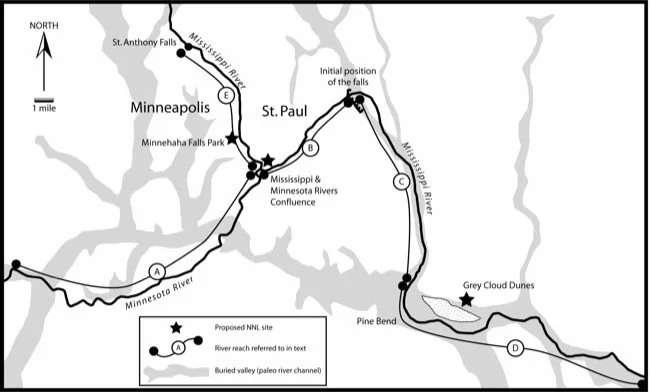

At the end of the Ice Ages, a glacial river cut its way through these stone layers creating stone bluffs and an enormous waterfall. The river split where Fort Snelling is now and again at Minnehaha Creek. Minnehaha Falls was created and began its own path. Saint Anthony Falls continued on its journey upriver. The repeating cycle of erosion and collapse moved the falls at an average of 4 feet per year.

So why haven’t they kept moving?

The Edge of Collapse

In 1869, A mill owner named W. W. Eastman got a little too greedy for water power and tried to dig a tunnel under Hennepin island. The excavators got more than they asked for and a huge swath of sandstone underneath the falls washed away. Massive pieces of limestone broke off and even a part of Nicollet Island collapsed. The entire mill community was in a panic, worried that the falls would continue to degrade and all of their waterpower would be lost.

The Army Corps of Engineers was mobilized to stabilize the falls. They built a cement cutoff wall, embedded in the sandstone. This three story wall, invisible to us, stopped water from eroding anymore of that crucial supporting layer.

It’s hard to overstate the effect this collapse had on Minneapolis and Saint Anthony. Not only did it physically alter the waterfall that was the center of its existence, but it also changed the structure of ownership. Up until the collapse, waterpower from the Mississippi River was privately owned by individual mills based on amount of land they owned on the riverbanks. They could use this waterpower themselves or lease it to other mill owners. This created the network of crazy tunnels that burrowed deep under the city streets.

After the government was required to intervene at the cost of the taxpayer, a new system of regulations and oversight was put in place. Private ownership of the waterpower came to an end and it became a public utility.

The Underlying Problem

Today, it has been brought to the city’s attention that no one seems sure what condition that cement cutoff wall is in or even who owns it and is responsible for its upkeep. Is it the responsibility of the city, county, state or federal government? Because of the speed and purpose for which it was built, there was no plan put in place for the future or even access built to physically monitor the wall. It is possible that the wall is in great shape, but no one knows for sure.

There’s a push at the state legislature to make SURE it is and make SURE there’s a plan if it isn’t. Since there is only a few hundred yards of limestone upstream, if the falls collapse they could be reduced to a long rapids. This would affect the water level and erosion for miles above and below the waterfall, which would affect our drinking water source, water power for electricity, bridge supports and the foundations of any buildings along the rivers’ edge.

Understanding the power and the fragility of the falls really helps us appreciate how important and powerful they really are.