Slavery in Minneapolis

The 6th Avenue Southeast sculpture walk is a fun chance to look at Saint Anthony landmarks. Some still standing - others long gone. One in particular, has an interesting story because its demise was due to the fight over slavery.

Minnesotans like to pride themselves on being from a northern, free or antislavery state. But it actually wasn’t. Even though slavery was illegal in the Minnesota territory, most of the officers at Fort Snelling had slaves at the fort. Many of the fur traders, including Henry Sibley, also owned slaves. In fact, one of the most famous slaves that ever lived - Dred Scott - was owned by the Army doctor at Fort Snelling, Dr. John Emerson.

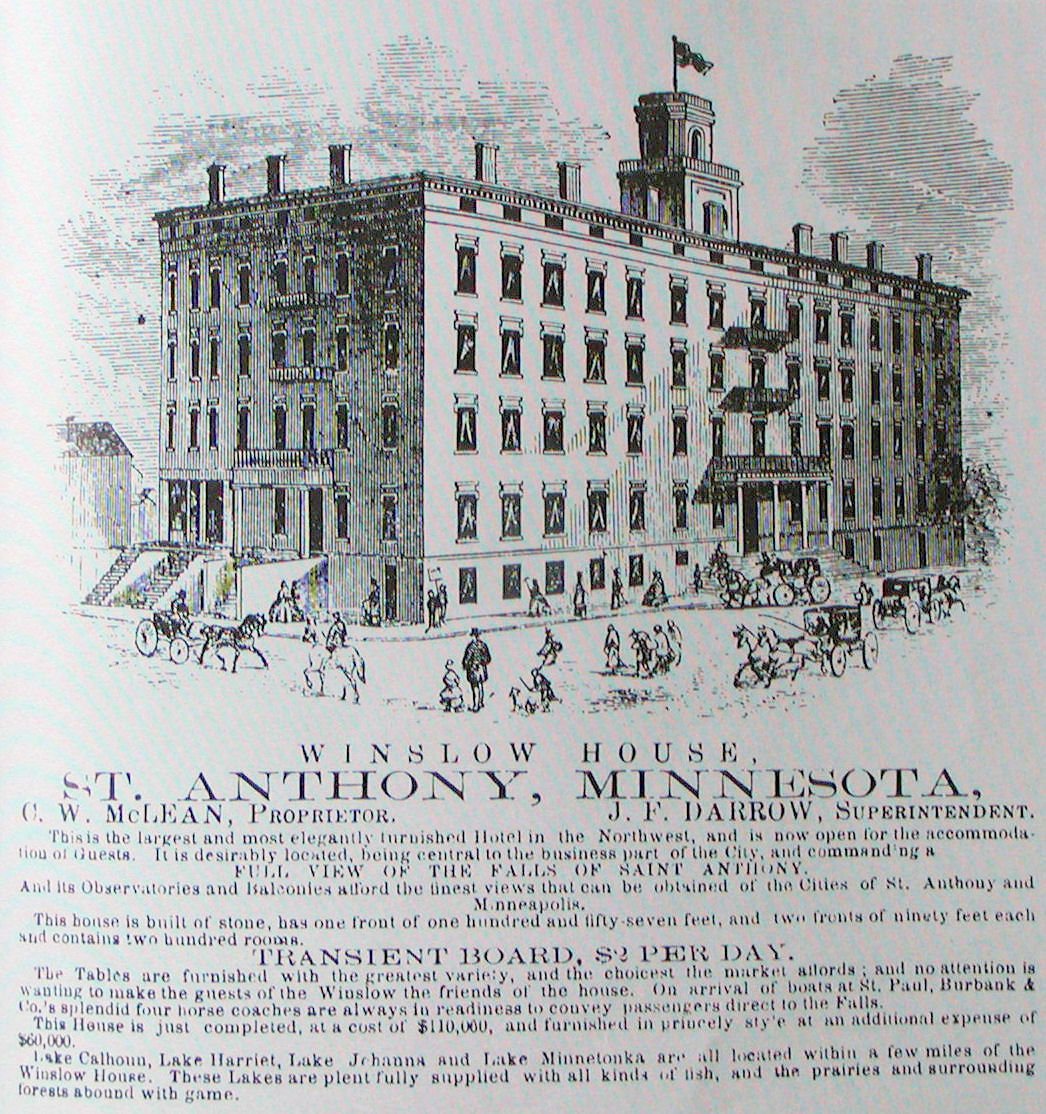

When Minnesota became a state in 1858, there was an end to Minnesotans owning slaves, but that didn’t stop tourists from out of state from bringing their own with them when they traveled up the Mississippi River on vacation. The Winslow House, an elegant hotel opened in 1857 in Saint Anthony and catered to southerners who didn’t want to travel without their household servants. The Christmas family, from Mississippi, came to Minneapolis in 1860.

Even though the Christmas family had brought their slave, Eliza Winston, to a state where slavery was illegal - she wasn’t automatically freed because she was their property. In the eyes of the law, she was comparable to furniture or luggage.

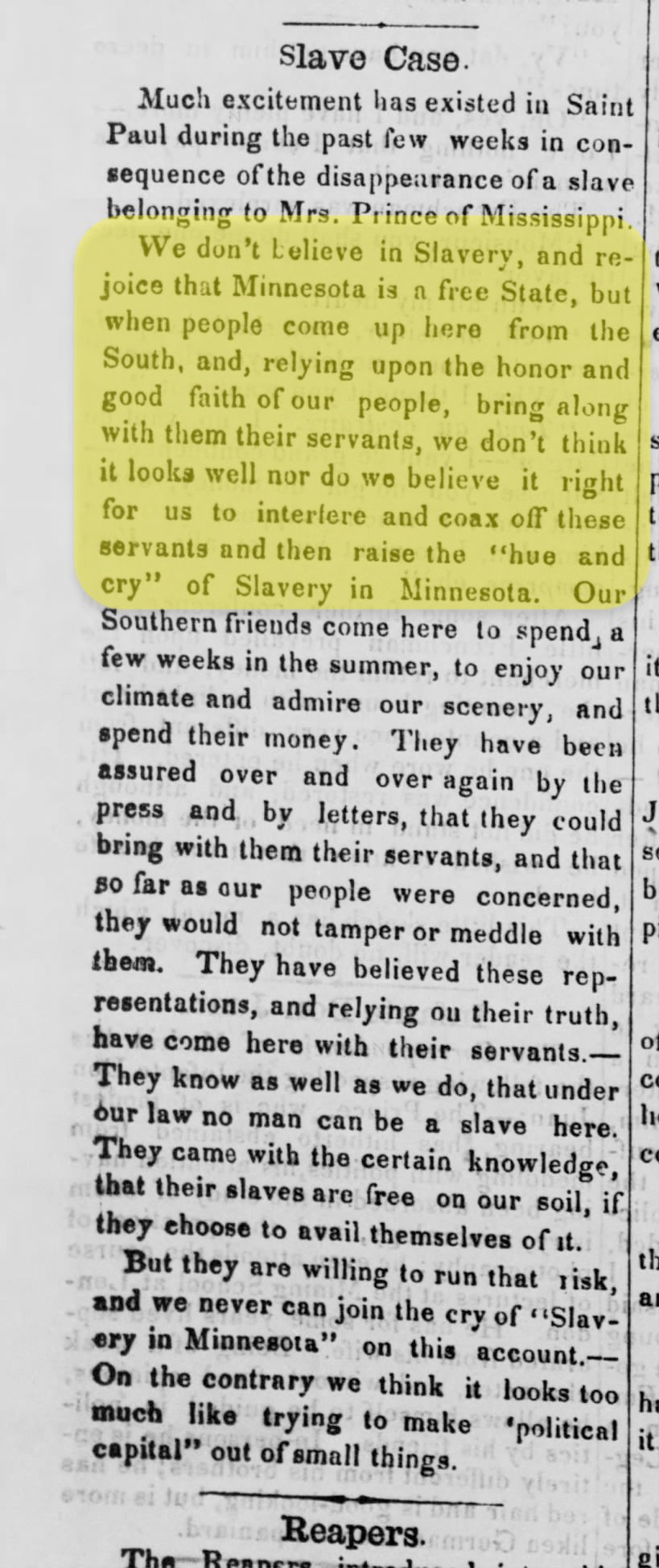

At the Winslow House Hotel, Eliza met a local abolitionist and former slave, Emily Goodridge Gray, who stood up for Eliza and filed a complaint to be heard in front of a judge. The case exposed Minnesota business owners’ hypocrisy: they were willing to accept slavery if it benefited their bottom line. The sentiment in favor of allowing slaves to be brought into Minnesota was so strong that over 900 Saint Paul, Minneapolis, and Stillwater business owners signed a petition pushing legislators to make it the law. It was never taken up by the legislature because they had bigger problems, like the Dakota War and Civil War.

The judge, however, granted Eliza her freedom and she was smuggled out of the city.

The Winslow House suffered immediately as other southern slaveholders were unwilling to take the risk of traveling to Minnesota and losing possession of their slaves. The hotel closed four months later and was later demolished.

Today, a condominium building near the location bears the Winslow House name and you would never guess at the tumultuous fight for freedom associated with the Winslow House name.

There is no clear end to Eliza’s story either. Some say she was assisted to Canada and started a new life there, but others say that she eventually returned to the Christmas family in Mississippi voluntarily because she couldn’t financially support herself and had no other options. Either way, her case revealed Minnesota’s complicity in the slave trade.