Slavery's Reach to the University of Minnesota

In a previous post, I shared the early financial struggles of the University of MN. Unfortunately, desperate to find ways to make ends meet, the Board of Regents made some questionable decisions about who to take money from.

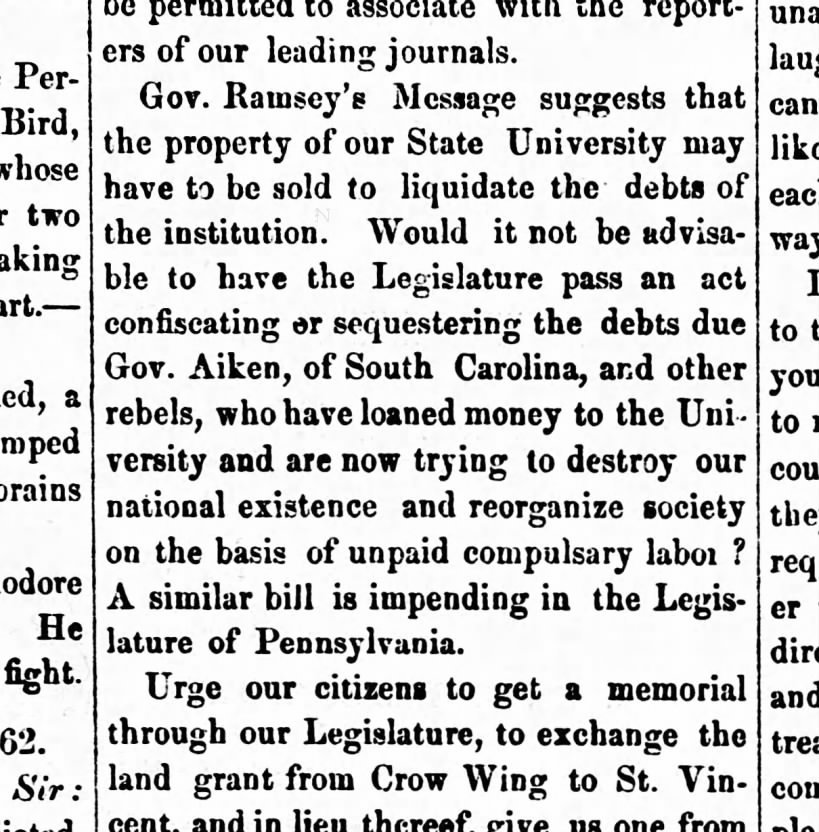

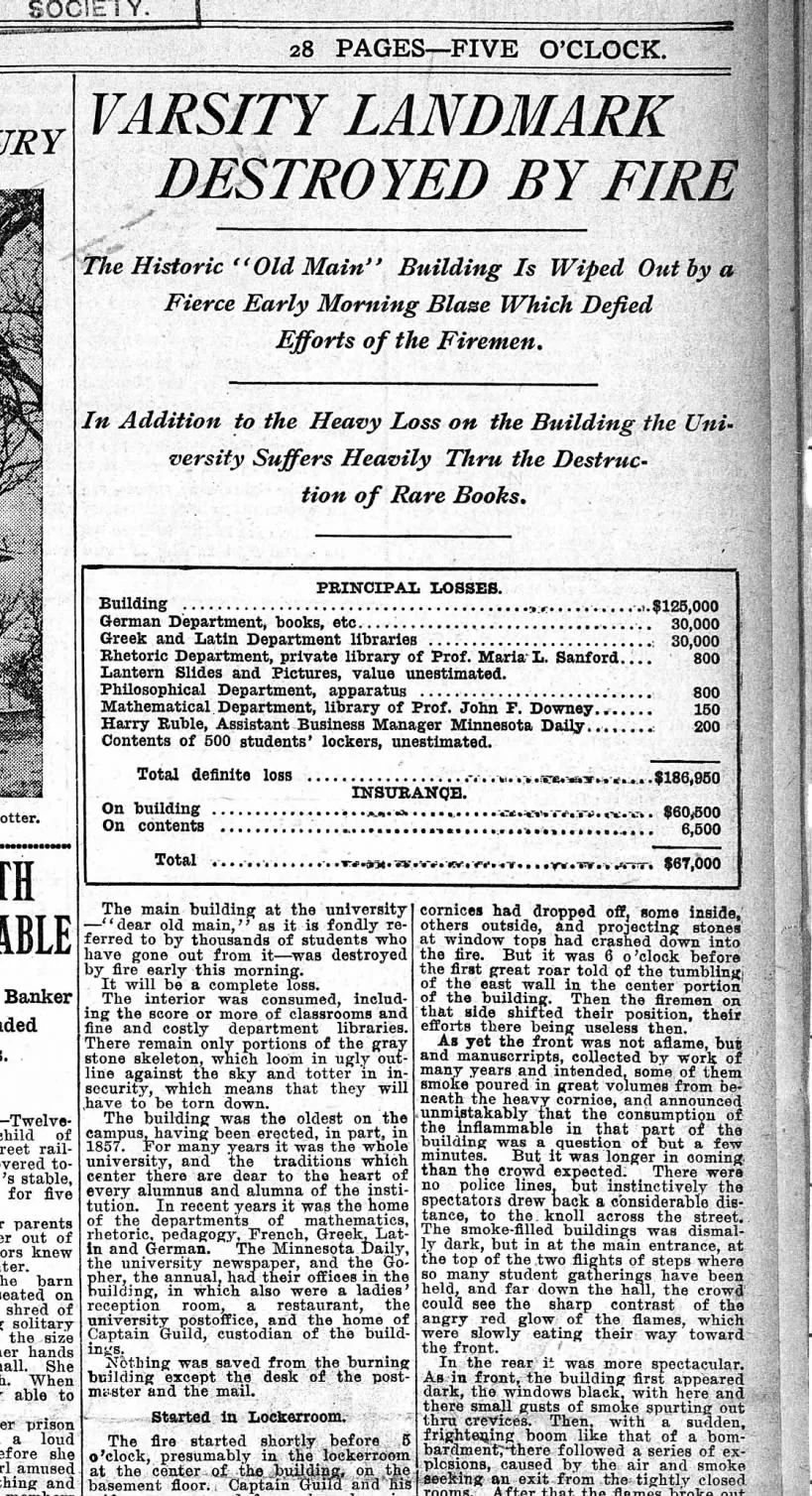

In 1856, the school was closed and deep in debt. They had begun building Old Main, but the cost was exceeding expectations. They had taken out loans to cover operating expenses. To pay off this debt, the state allowed the Board of Regents to sell up to $40,000 in bonds. Bonds are basically a GoFundMe, but you are required to pay it back.

Henry Mower Rice, convinced his friend and politician from South Carolina, William Aiken, to buy almost $15,000 of those bonds. This meant that 40% of University was being funded by a slaveholder.

William Aiken, Jr.

William Aiken, Jr. was a powerful man. He had served as both a state senator and state representative for South Carolina. Then he was the governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844. While serving in the United States House of Representatives, Aiken started coming to Minnesota to escape the brutal southern summers. Back home in South Carolina, Aiken owned over 700 slaves and it was the profits of their labor that allowed him to loan the University money. At the time, these types of financial arrangements were highly encouraged. Many hoped that these North/South partnerships would help tamper down the animosity created along political lines.

A year later, the University paid Aiken back about half of his loan and Aiken used the money to renovate his mansion in Charleston, The Aiken-Rhett House.

The Aiken-Rhett House

When the Civil War began, the University still owed Aiken $7000. Although Aiken actually sided with the Union, his reliance on slave labor was still an issue and the Board of Regents quietly converted the outstanding balance from a loan to a donation.

The St. Cloud Democrat, February 20, 1862

Isabell Kall

As young woman Isabell Kall (whose family owned slaves in Maryland) had visited Minnesota as a child. After she inherited her family’s estate she invested it and also purchased $7000 in bonds to support the University. When it was time to pay her back after the Civil War, she was living in Washington, DC (a Union city) so she could not be deemed a Confederate rebel. The University couldn’t get out of paying her back. John Nicols, a University of Minnesota Regent and a a slaveholder from Maryland, was sent to negotiate with her and they agreed on a repayment plan. She earned nearly $3300 in profit on her investment.

Board of Regents Annual Report, 1867

The University wiped these connections away and the official history thereafter focused only on how John S. Pillsbury’s leadership and financial donations saved the University. In reality, without Aiken and Kall and their profits from slaveholding, there wouldn’t have been a school to save.

So what?

You might be thinking, “$15,000? $7000? Who cares? That’s just a drop in the bucket now.” But at the time, those two donations equated to more than SIXTY PERCENT of the University’s budget.

So what does this mean? Does this make the U complicit in slavery? Does this mean the University owes something to the descendants of slavery? Should the University’s published history acknowledge the connection? Has the University done enough in terms of Affirmative Action policies or scholarships to balance the scales?

If you are interested in reading an in depth history of the southern slaveholders who invested in, vacationed in, and financially influenced early Minnesota - check out Slavery’s Reach by Christopher Lehman. It is a very revealing read that gives a very different version of our early Minnesota “heroes” whose connections to slavery have been erased or hidden.