Can a Rock Be Racist?

Are you on NextDoor? Have you heard of this app? We joined it just before the pandemic and I thought it was fun, quirky, and an interesting way to interact with our neighbors (without having to actually talk to them).

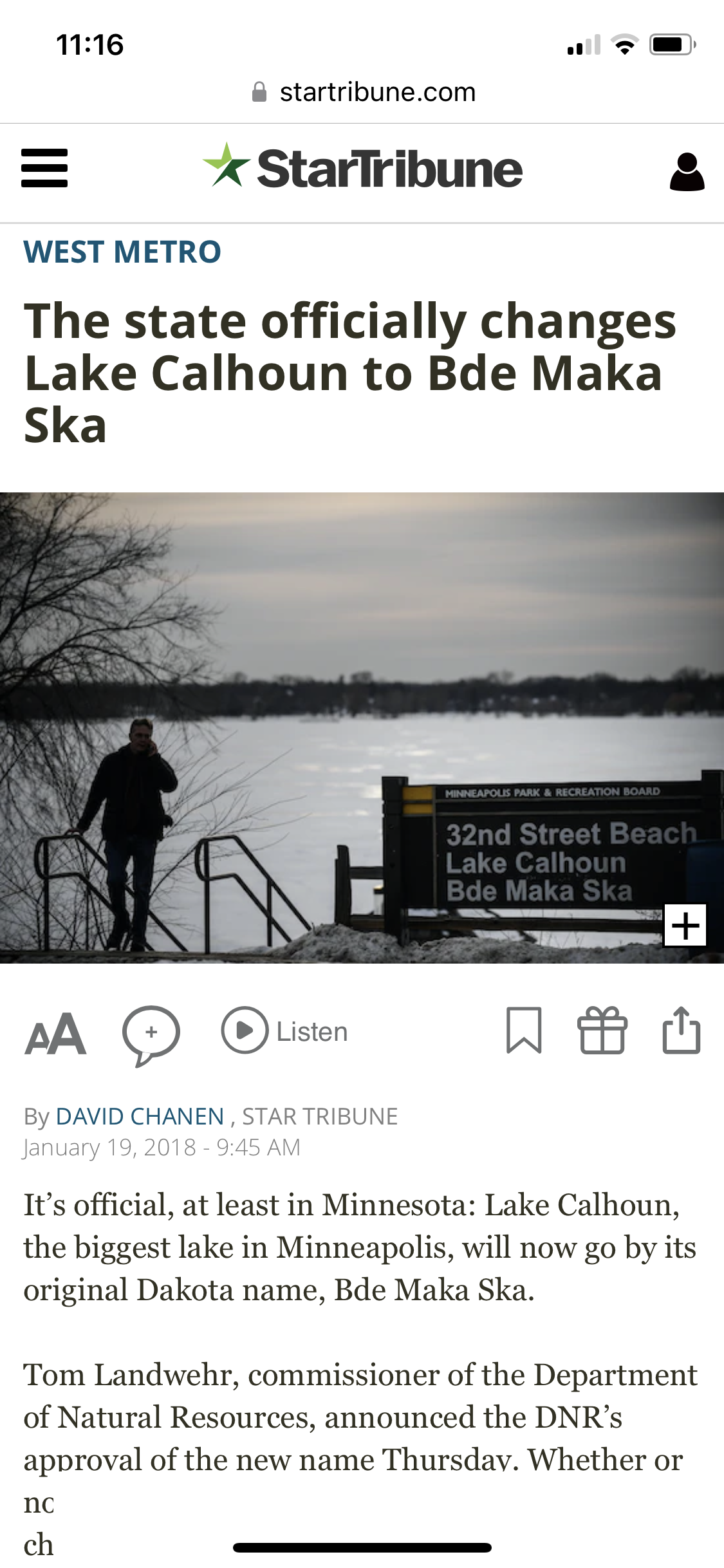

A few months ago, someone asked the question, “Racist boulder memorial Bde Maka Ska. Does anyone know of an organized effort to remove this racist boulder memorial from the east side of Bde Maka Ska? I contacted my park board representative a few months ago about it but never heard back.”

What followed was a mish-mash of knee-jerk responses, attempts at clarifications, rude and dismissive quips, and a few rational replies. It spun out of control several times as people began to comment without reading previous replies. Emotions ran high. Apologies were made. It was very dramatic.

And then nothing. I’m sure that the few posters that proposed follow up with the parks department, Dakota organizations or the Historical Society may have actually done so, but they never reported back to the group. So I was left hanging!

I had to do some digging myself, and of course, fell down a rabbit hole that included reading the entire autobiography of Samuel and Gideon Pond, scouring newspapers from 1905 through 1930, and digging through the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society. I reached out to the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council and the Native American Initiatives Department at the Minnesota Historical Society. I’m not sure I have any more answers now than before I began.

MEET ME AT THE ROCK

This sad rock, that no one really notices, is just on the edge of a bike path around Bde Maka Ska. The rock is sinking into the ground and the plaque is hanging on by only two screws. The plaque on the rock reads:

“On the hill above was erected the first dwelling in Minneapolis by Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond, missionaries to the Indians, June 1834. Dedicated by the Native Sons of Minnesota, May 30, 1905.”

Seems pretty straight forward, but dang if it’s not. The first question is: who were Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond?

THE BROTHERS

Until their twenties, Samuel and Gideon Pond were pretty average boys living in Connecticut.. They were both apprenticed out in their teens and learned trades (fabric dying and carpentry) as well as how to farm. Neither were very successful. Gideon was small for his age, so the work was too much for him. Samuel suffered a major illness, perhaps rheumatic fever, that left him very weak.

During the Second Great Awakening, which spread Protestant religion through tent revivals and emotional preaching, both brothers were inspired to head West to spread Christian teachings. In 1833, Samuel left home, first to Galena, Illinois and was met there later by his brother.

They were not officially missionaries. They were not ordained and didn’t actually have any support (they did both become ordained and officially supported a few years later). They didn’t even have permission to be on Native American land - they had to get it at Fort Snelling. When they appeared there before Major Bliss, Samuel admitted that he “had no plan except to do what seemed most for the benefit of the Indian.” Since they did have experience as farmers they were given the assignment of teaching the Dakotas how to use a plow and team of oxen, first with Little Crow at Kaposia and then with Cloud Man on the shores of Bde Maka Ska.

CLOUD MAN VILLAGE

There was already a village there when they arrived, called Ḣeyata Ọtunwe (village to the side). While teaching the Dakota to plow their corn fields, the brothers formulated a plan to learn the Dakota language. They believed that learning it, and learning the Dakota culture as well, would help them better reach them and convert them to Christianity.

In 1834, the brothers were given permission from Fort Snelling to build a cabin in Cloud Man’s Village. The chief, himself, suggested the plot at the top of the bluff that would overlook the village and lakeshore. This spot is reportedly where St. Mary’s Greek Orthodox stands today.

Samuel describes: “The village, which stands on the southeast side of the lake, consists of fourteen dwelling houses, besides other small ones. The houses are large, and two or three families live in some of them. You would not see our house from the village, but, turning to the right along the east bank of the lake and ascending a hill, after walking about a quarter of a mile, you would find our house on the high ground…”

So, their cabin was NOT the first dwelling in the area and they knew it. They never said it was. However, other people started referring to it as such almost immediately and the Pond’s didn’t correct them. The American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions referred to it as “the home of the first citizen settlers of Hennepin County, perhaps of Minnesota; the first schoolroom, the first house of divine worship, the first mission house among the Dakotas.” The implication being, they were citizens because they were white. The Dakota were not citizens.

Only a couple years after building their cabin, the brothers were asked to move in with Jedidiah Stevens and his family on the banks of Lake Harriet (Bde Unma) and help establish a mission and school there. The cabin on Bde Maka Ska was torn down when the Dakota battled the Ojibwe in 1839 and needed the wood to build defenses. So, it actually only stood for about 5 years.

BACK TO THE ROCK

So, in that context, going back to the rock and rereading it:

“On the hill above was erected the first dwelling in Minneapolis by Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond, missionaries to the Indians, June 1834. Dedicated by the Native Sons of Minnesota, May 30, 1905.”

It wasn’t the first dwelling in MINNEAPOLIS (in fact, Minneapolis didn’t even exist yet), but grammar matters. It WAS the first dwelling in what would become Minneapolis BY Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond. So, if we read it in that context it would seem to be correct. It slightly misrepresents them, but they are facts. So far.

Second question: The rock says that they were missionaries to the Indians? What exactly does that mean?

STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND

There is a lot of debate now about the role or benefit of missionaries, evangelism, and “voluntourism” today. People are much more sensitive to cultural appropriation and discrimination. We have also come to understand (or at least I hope we have) that presuming that your culture or religion is “better” or “the correct” culture or religion, is no longer acceptable. There is a hard line between believing in your religion and enacting laws or social structures that force others to believe in it too.

These views were definitely not the norm in the Pond brothers’ lifetimes. They believed with all of their hearts that the Protestant Christian faith was the ONLY way to heaven and they were passionate about helping others find that path. They weren’t alone either. Dozens of missionaries moved westward as more and more territory opened up.

Describing the Dakota before they arrived at Fort Snelling, Samuel wrote:

“It was to a people ignorant, savage, and degraded, and, as (we) had been led to believe, to a dreary region where the people clothed themselves in furs and were little better off than exiles to Siberia.”

They referred to them as “heathens” and “savages”. They purposely ignored the native dances and rituals, refusing to acknowledge the native faith. The Pond brothers’ writings have several references describing the Dakota as rude, beggars, drunks, thieves, and liars.

The “mission” of the missionary society that the Pond brothers subscribed to was not just to change the religion of the Dakota. They demanded that the Dakota give up hunting and warfare, cut their hair, wear european clothing, destroy ritual objects, and give up plural wives. They asked that the Dakota abandon everything that made them Dakota. The underlying motive was that the brothers foresaw no future where the Dakota could maintain their traditional lifestyle and successfully assimilate into advancing American culture. They believed that they were helping Native Americans to “rip off the bandaid” so to speak, and become active members of the advancing colonial society. Unfortunately, they were blind to their acts aimed at eliminating an entire culture.

To put it in today’s terms, what the Pond brothers did in 1834 was the definition of “white male privilege”. They had no qualifications, no money, no permission, yet they showed up in Native American territory and were given free rent, free food, jobs and authority and imposed their beliefs and culture on one that they considered inferior. Their goal was to eliminate and obliterate any remnant of Native American history, religion, or way of life. But in that time, in that place, their actions were accepted as completely normal, their beliefs were the beliefs of the dominant white Americans and they were supported in their efforts by the United States Government.

THE GOOD THEY DID

Before the missionaries the Dakota language was unwritten. The Pond brothers worked for years to first learn the Dakota language, then created an alphabet to be able to write it. They used the Pond Alphabet to teach the Dakota how to read and write. They collaborated with other missionaries to the Dakota, Stephen R. Riggs and Thomas Williamson to create a dictionary of the Dakota language. They also published reading lessons, chapters of the bible, even a regular newspaper, called “The Dakota Friend” in the Dakota language. In this way they helped some Dakota learn to read and write their own language and then to learn to read and write in English. They were the first white men to record and translate the Dakota language. It wasn’t perfect and there are many examples of them not quite getting the translation right, but it went a long way towards helping the Dakota learn English and reduce their chances of being taken advantage of by English-only settlers, the government, and traders.

After many years of living among the Dakota, Samuel wrote a book detailing the Dakota way of life including their religious beliefs, social structures, habits, clothing, and more. Samuel’s views about the Dakota had clearly changed. He wrote that the Dakota were “equal to the white man” and “a race worth preserving”. He wrote several passages defending them against racist stereotypes. Ironically, in their efforts to study the Dakota in order to convert them the Pond Brothers became some of the most active preservationists of their language and culture.

GOING THEIR SEPARATE WAYS

The ongoing conflict between the Dakota and the Ojibwe flared up again in 1839 and it was too much for the brothers. They had both been ordained by then and sought out ways to better make the difference they so desired, to bring souls to Christ. Gideon built a home and church in Bloomington and served in the territorial legislature. Samuel stayed with the Dakota when they moved to Shakopee, but when the Dakota were forced out of the state in the 1850s, he decided not to follow them. After that, they both focused on serving the white settlers coming to the area. Their congregations did include native americans, as long as they were “converted”.

NATIVE SONS

Back to the rock.

“On the hill above was erected the first dwelling in Minneapolis by Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond, missionaries to the Indians, June 1834. Dedicated by the Native Sons of Minnesota, May 30, 1905.”

The Pond brothers built a dwelling on the hill, it was the first dwelling they built, and they were missionaries to the Natives. “Missionary” is a loaded word that doesn’t really reflect the complexity of Samuel and Gideon’s relationships with the Dakota. However, the inscription doesn’t portray them as heroes or claim that they “saved” anyone. But it doesn’t have to explicitly SAY that they’re heroes, if the implication is that they were. So the next question is: who were the Native Sons of Minnesota and why did they put up this memorial to the Ponds?

In the early decades of the Minnesota Territory and the state of Minnesota there was no infrastructure to record the population - no birth or death certificates, no government identification, no census bureaus. It was up to the settlers to just remember and the government took them at their word. On March 4, 1870, a law was passed requiring the official recording of births and deaths in Minnesota. Those that hadn’t been recorded could submit their information to the Native Sons of Minnesota Vital Statistics. In 1902, an organization formed to further this effort - the Native Sons of Minnesota. This fraternal organization was open to anyone born in Minnesota before 1870. According to an article in the Minneapolis Journal, November 1, 1902, their aim was to

“inculcate and foster a spirit of loyalty and love for Minnesota, arouse a state pride, perpetuate the names and deeds of the early pioneers and make known the glorious history of Minnesota.”

That sounds great, right? The first settlers were aging or dying and this generation wanted to make sure that their efforts in building the state of Minnesota were remembered. That sounds like a fine sentiment until you read further. The language of this article continues to reveal that the aim of the Native Sons is to remember:

“the pioneers who transformed the primeval forests of Minnesota into smiling fields”, and “stayed the advance of the red horde”.

They may have called themselves “Native Sons”, but Native Americans were not welcome.

In the end, their work didn’t amount to much. In addition to the plaque commemorating the Pond’s cabin, they dedicated a park to Peter M. Gideon who cultivated the first variety of apple that would grow in Minnesota’s climate. They dedicated a plaque to Jedidiah Stevens and Gideon Pond at the site of the school and mission they built on Lake Harriet. They organized celebrations for the 50th anniversary of Minneapolis and the 100th anniversary of Fort Snelling. They hosted banquets and picnics and then sort of faded away.

BEYOND THE ROCK

The plaque on the rock is not the only structure in honor of the Ponds. A replica of Gideon Pond’s 1855 house in Bloomington serves as a museum and hosts Dakota language learning camps and classes. Oak Grove Presbyterian, the church Gideon founded, is also still there, although it has been rebuilt over the years. An elementary school was also named in his honor in Burnsville, Minnesota.

As for Samuel, his home in Shakopee no longer stands but the foundations of the home are part of a larger Memorial Park. The park also includes Native American burial mounds and a trail with educational plaques. There are sculptures of both Chief Sakpe, Shakopee’s namesake, and Samuel at the River City Centre. The church he founded, First Presbyterian, also still stands.

THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTION

We’ve learned a lot of information that the plaque doesn’t provide. There were dwellings at the lake before the brothers built their cabin. The Ponds were missionaries, but that one word cannot describe the complex relationship that they had with the Dakota. Their aim was to abolish a culture, but some of their work helped insure its survival. The plaque was erected by an organization motivated to remember a specific version of history that excludes what we’ve learned. They sought to remember a history of Minnesota that began when white people arrived.

The most important fact that we have not learned is what do the Dakota think of the Pond brothers? Do they regard the relationship as a positive addition to their history or do they regard the Ponds as a part of the story of their oppression?

I reached out to, but haven’t heard back yet, from the Historical Society or Council, about how the Dakota view the representation of the Pond brothers in Minnesota history . When I do, I will be sure to update this post.

SHIFTING BALANCE

A stone’s throw away from the Pond rock at Bde Maka Ska is a public art project installed in 2018. Titled Brave Change (Zaníyaŋ Yutḣókc̣a), the project commemorates Cloud Man’s village as it stood on the banks of the lake. An iron railing incorporates the corn, squash and beans they farmed; the birds, turtles, and other animals they encountered; the wild rice that used to grow in the lake. Stamps were used to imprint images into the sidewalk of other animals and plants beside what they are called in the Dakota language.

Interestingly, the project also encompasses a pre-existing plaque that reads:

“To perpetuate the memory of the Sioux or Dakota Indians who occupied this region for more than two centuries prior to the treaties of 1851. This tablet is erected by the Minnesota Society of Daughters of the American Colonists, 1930."

There are no clear cut answers here. The story of the Pond brothers is inextricably linked to that of the Dakota. The Pond Alphabet has helped create a continued path to learning the Dakota language. Today, the Pond House hosts Dakota language learning camps for kids. Until now, their story has been the headline and the story of Cloud Man and the village at Bde Maka Ska were just supporting facts. Since 2018, with the movement to rename the lake and build the public art project, the story has become more balanced.

In my opinion, and this is just my opinion, the plaque at Bde Maka Ska should either be removed (letting Bde Maka Ska be a Dakota focused site) or be replaced and updated to reflect that the Ponds accomplished what they did here because of the kindness, support, and collaboration of Cloud Man and the Dakota. There are so many other more accurate representations of the Pond brothers that an inaccurate plaque at Bde Maka Ska seems superfluous.

LEARN MORE

If you are interested in learning more about Bde Maka Ska, I highly suggest watching “Ohiyesa: The Soul of An Indian” on Amazon Prime (this is NOT an ad, I just really liked this film). You can rent it for $2.99. It follows Dr. Kate Beane and her family as they discover and document their ancestor, Ohiyesa. Ohiyesa was the great-grandchild of Cloud Man and lived through some of the most tumultuous events for the Dakota. As an adult, he took the english name Charles Eastman and became a celebrated doctor and author. His books are still available today.

The movie also documents Dr. Beane and her families efforts to restore the name, Bde Maka Ska, to the lake. It is a beautiful film and you will never see the lake the same way after watching it.

THOUGHTS?

So what do you think after taking in all this information? What should be the future of the rock: leave it, restore it, replace it, remove it? There are no wrong answers - as long as they’re respectful. Let me know in the comment section!